Extreme Climate Survey

Scientific news is collecting readers’ questions about how to navigate our planet’s changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

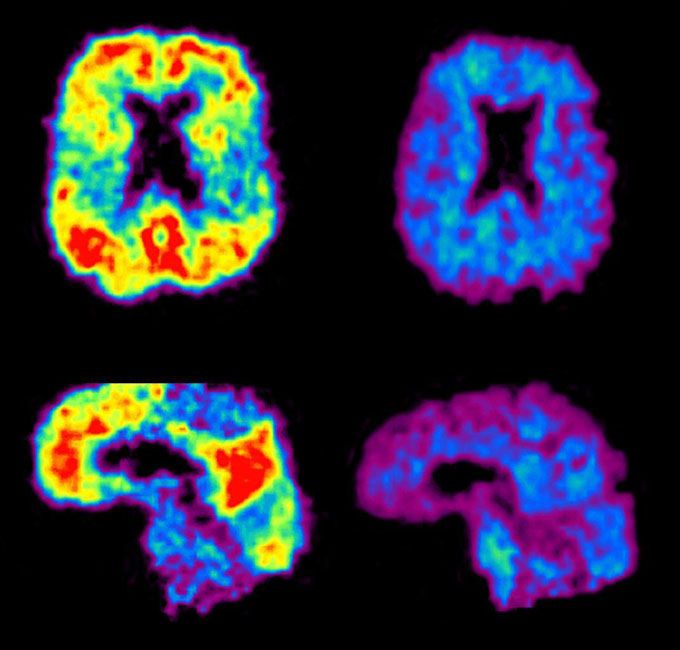

But spinal taps and brain scans are expensive and uncomfortable. Taking blood would lower the barriers to diagnosis even more. That matters because while Alzheimer’s has no cure, an easier and faster way to spot the disease could give people more time to discuss therapy options, including newly available drugs that lower levels of of amyloid, the sticky protein that accumulates in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. (SN: 17.7.23). These drugs moderately slow the progression of the disease, but they come with serious side effects (SN: 6/7/21).

“It’s an exciting time,” says neuropathologist Eliezer Masliah of the National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Md. “It’s an explosive moment,” one that has the potential to help reshape the diagnosis and treatment of the nearly 7 million people with Alzheimer’s in the United States and millions more worldwide, he says.

However, many questions surround these new blood tests, warns Masliah. Such tests are now available, but none have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. And their utility for testing people before any symptoms appear is being studied. “We’re at an early stage right now.” If past Alzheimer’s research is any indication, the answers won’t be simple or quick.

Right now, it’s clear that the landscape is changing rapidly, and scientists and doctors are bound to learn more about the disease as blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease gain more attention. Here’s what we know about the tests so far.

Do blood tests for Alzheimer’s work better than current ways to diagnose the disease?

Without specialized brain scans or cerebrospinal fluid tests, doctors are not that good at diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. A study of 1,213 people in Sweden found that primary care doctors were correct – both in identifying and ruling out Alzheimer’s – only 61 percent of the time. These results were presented at the AAIC meeting in Philadelphia on July 28 and published the same day JAMA.

“It’s not that we think primary care doctors don’t do a good job. They do,” says Oskar Hansson, a dementia researcher and neurologist at Lund University and Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden. “It’s that the tools they have today aren’t good enough.” Even dementia specialists didn’t fare much better: they were right 73 percent of the time.

But a blood test can help increase this accuracy. In the recent study by Hansson and colleagues, a blood test that measured two ratios of Alzheimer’s-related proteins (the amyloid and tau versions) in people’s blood was 91 percent accurate. This is a big difference from the accuracy of doctors, when even specialists misdiagnosed about 1 in 4 patients.

The results are important because they address how a blood test works in a real-world setting, says neurologist and Alzheimer’s researcher Stephen Salloway of Brown University’s Warren Alpert School of Medicine in Providence, RI. this test in primary care,” he says.

The results also promise to get people to a diagnosis much faster. Right now, a person who goes to their doctor with memory or thinking problems can spend months or even years waiting for appointments and tests that yield an Alzheimer’s diagnosis. By the time they are diagnosed, their symptoms may be too advanced to benefit from new treatments, says JAMA Study co-author Suzanne Schindler, a neurologist and dementia specialist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “We see this all the time … they’ve come too late.”

What exactly do these blood tests measure?

There are many potential markers for Alzheimer’s disease circulating in the blood. And scientists are studying many of them (SN: 2/1/18). But one particular marker has attracted a lot of attention recently: a protein called p-tau217. “I think it’s clear now that p-tau217 is really a fine biomarker of amyloid plaques,” says Schindler.

Tau is a protein that has long been known to form tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. Like any protein, tau is made up of a string of amino acids, some of which can be decorated with chemical tags. That “p” in p-tau217 means that one of the amino acids in the tau protein (the 217th, actually) has been decorated with a phosphate group—a modification called phosphorylation.

Some blood tests measure p-tau217 levels themselves. But the test used in the latest study included the ratio of p-tau217 protein to tau that is not phosphorylated at point 217. This ratio may be more accurate than measuring just one version of tau, because diseases other than Alzheimer’s can affect overall tau levels. , says Schindler. The test also included a ratio of two types of amyloid protein.

These ratios in the blood indicate the amount of amyloid plaques in the brain. (The reports also correlate well with disease markers in the cerebrospinal fluid.)

Can Alzheimer’s Blood Tests Stand Alone? Will they be the final word on a diagnosis?

No. Blood tests give part of a person’s overall clinical picture. There are many reasons why a person may have cognitive problems, such as drug side effects or sleep problems.

“I think it’s important not to attribute all symptoms to Alzheimer’s disease because someone has a positive test,” says Schindler. “I can’t cure their Alzheimer’s disease, but I can stop the drugs that are causing problems, or I can diagnose their sleep apnea, or I can do other things that are helpful.”

Are these tests available now?

yes. “Of course people are using it there,” says Masliah.

But blood tests are not necessarily thoroughly tested for accuracy. In a head-to-head comparison of six commercially available tests, tests that used p-tau217 accurately identified signs of Alzheimer’s disease, specifically amyloid accumulation on a PET scan, Schindler and her colleagues found. This work was described in a preprint on medRxiv.org and presented July 30 at the AAIC meeting.

No blood test for Alzheimer’s has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Salloway points out that FDA approval is not necessary for use, although it can inspire confidence in the results. Schindler says he wouldn’t be surprised if FDA approval happens next year for one or more of these tests. But it’s not clear whether insurance companies or government-provided health care programs will routinely cover these tests.

What’s next for Alzheimer’s blood tests?

There are still many unknowns, including whether these tests work well for different populations around the world. “You can always do more research that can prove it even more,” says neurologist Sebastian Palmqvist of Lund University and Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden, who co-authored the JAMA paper. “In Sweden, we feel very comfortable, at least in specialized settings, to start using this test.” This may not be the case for other countries and groups of people.

Another missing piece is the standardization of these tests. There are still no guidelines that would help doctors know when to use them and how to interpret the results.

“There’s a lot of data already that this would be an excellent indicator,” says Masliah. “But we still need that last piece to have the actual guidelines. Without this it would be the wild west. You can interpret the results in any way you want. That wouldn’t help anyone.”

Guidelines, similar to those that exist for cholesterol levels, will need to be developed before these tests are widely useful, he says.

#Alzheimers #blood #tests #improving

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org